Executive Summary

Southern California's logistics, warehousing, and distribution sectors have driven significant economic growth, particularly in the Inland Empire region. However, this rapid industrial expansion has also resulted in increased environmental, traffic, and public health concerns, particularly affecting communities near these developments. To address the negative impacts on sensitive receptors such as residential neighborhoods, schools, and healthcare facilities, Good Neighbor Guidelines (GNGs) have emerged as an essential policy tool. These guidelines aim to mitigate the adverse effects of logistics and industrial developments, focusing on reducing noise, diesel emissions, and other environmental disruptions to surrounding communities. The recently enacted AB 98 exemplifies these efforts through state-level legislation, which has sparked significant debate, particularly in the Inland Empire region.

This case study explores the evolution and implementation of Good Neighbor Guidelines across six localities in the Inland Empire, including the Western Riverside Council of Governments (WRCOG), Riverside County, and the Cities of Riverside, Fontana, Moreno Valley, and Lake Elsinore. Through content analysis, researchers systematically reviewed these policies to identify key themes, such as air quality management, truck route planning, and noise reduction. The study highlights how each locality’s guidelines prioritize different aspects of community protection, reflecting their unique local priorities.

California’s local Good Neighbor Guidelines are framed around two key policy dimensions: local environmental protection and the preservation of community character. While the local environmental frame focuses on mitigating the externalities of industrial activity—such as air quality degradation and noise pollution—certain guidelines, like those of the City of Riverside and Lake Elsinore, are simultaneously framed to protect the residential character of neighborhoods, thereby supporting broader city planning efforts.

I. Introduction

Southern California’s rapid industrial growth, particularly in logistics, warehousing, and distribution sectors, has brought significant economic benefits to the region. Specifically, the logistics and warehousing sectors have significantly shaped the Inland Empirs economy, contributing to its growth as a pivotal hub for transportation and distribution in Southern California (Jaller et al, 2020). However, the expansion of these industries has also raised environmental, population, and public health concerns. In Inland Southern California, the logistics and warehousing sector poses unique challenges related to traffic congestion, environmental impacts, and community disruption (deSouza et al, 2022). To address some of the more adverse effects of industrial developments on localities and communities, particularly those with a high concentration of sensitive receptors like schools, residential areas, and healthcare facilities, good neighbor guidelines (GNG) have emerged as a critical policy tool at the local governments.

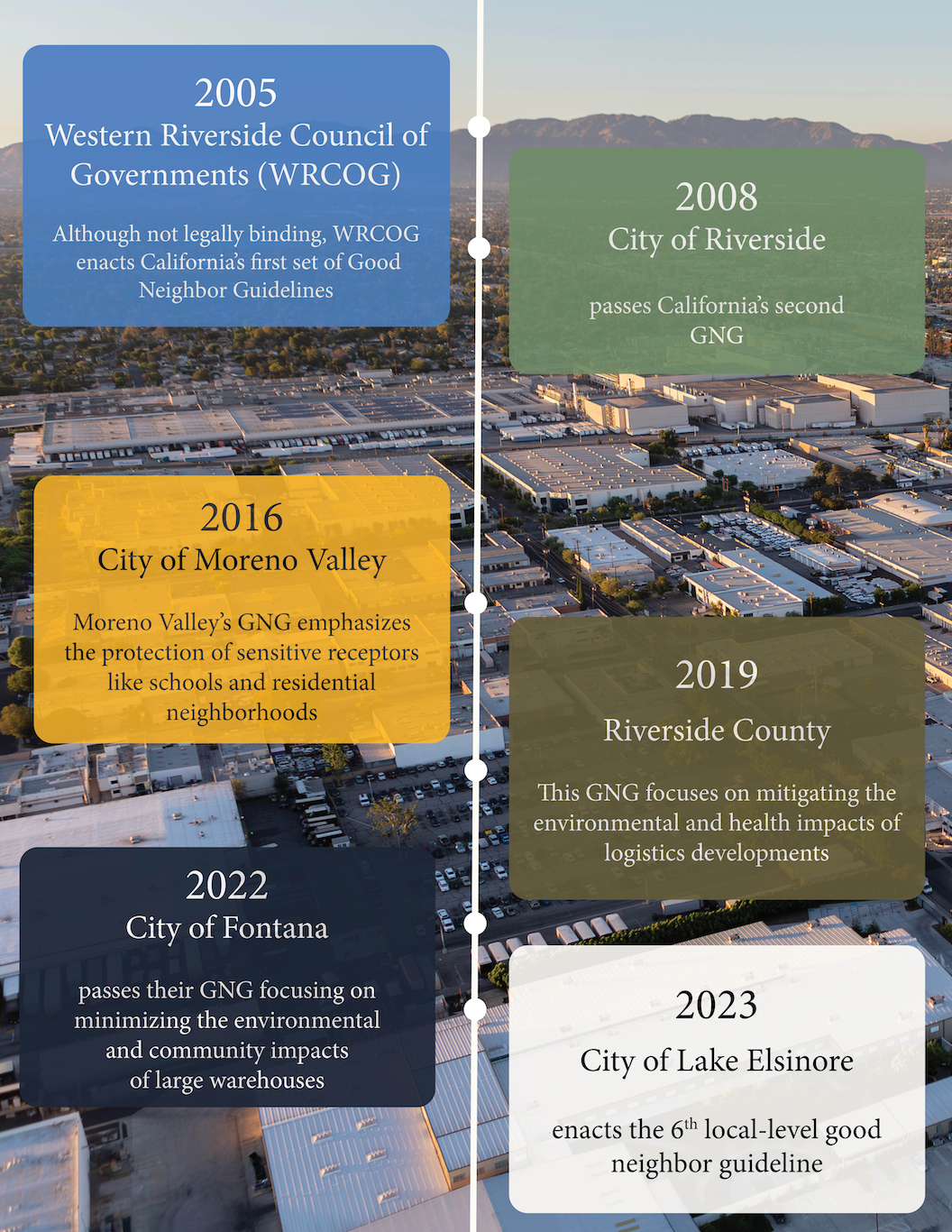

Good neighbor guidelines represent a set of local policies designed to balance economic development with the well-being and quality of life of surrounding communities. These guidelines typically address key concerns such as air quality management, noise reduction, and traffic control, particularly in areas impacted by industrial or trucking activities. They also emphasize community health and safety by limiting exposure to environmental hazards and promoting measures to protect public well-being. By tailoring land use and zoning practices, these policies aim to ensure industrial or commercial operations do not disrupt residential or sensitive areas. By reflecting the unique priorities of each community, these guidelines can serve as a framework for fostering accountability and safeguarding quality of life while supporting sustainable development (González et al., 2014). Since the enactment of California’s first good neighbor guideline by WRCOG in 2005, five additional California localities have adopted similar local level policies In addition to local level guidelines, a statewide good neighbor guideline, Assembly Bill 98 was signed into law in September of 2024. Figure 1 (included below) provides a timeline of each of the six GNG policies.

Much like the significant contrast between the opportunities and challenges posed by the development of the logistics and warehousing (LW) industries (Wang & Kopko, 2024), various stakeholders—such as government entities, the private sector (particularly within the L&W industries), and local authorities—hold differing views on the adoption and implementation of Good Neighbor Policies (GNP). For example, California Governor Gavin Newsom's recent signing of Assembly Bill 98 (AB 98) has ignited significant debate among various stakeholders. The legislation introduces statewide design and operational standards for new or expanded logistics facilities, including warehouses, with the aim of mitigating environmental and community health impacts. Supporters highlight its potential to reduce emissions, protect public health, and address environmental concerns, particularly in areas like the Inland Empire. Critics, however, argue it may hinder economic growth by increasing costs and regulatory burdens, undermine local autonomy in planning, and pose significant implementation challenges for businesses and governments.

In this context, the Center for Community Solutions is conducting a research project to provide an in-depth analysis of California’s local Good Neighbor Guidelines (GNG) in relation to the development of logistics and warehousing (LW) industries. As the first phase of the study, the current report focuses on an analysis of California’s six local-level good neighbor guidelines from the following municipalities in Inland Southern California: (i) the Cities of Fontana, (ii) Lake Elsinore, (iii) Moreno Valley, and (iv) Riverside, (v) the County of Riverside, and (vi) the Western Riverside Council of Governments (WRCOG). The second phase of the study will focus on the newly enacted state law, AB98, and will be published in a subsequent report.

We obtained each GNG from its respective city, county, or state website. Each document was analyzed through content analyses. Specifically, reading word by word, the researchers (including two undergraduate students and one staff member at CCS) assigned codes to passages based on key themes and issues identified within each document, enabling systematic and constant comparisons across different policies. This process allows for a comparison of the guidelines' varying emphasis on issues like diesel emissions reduction, truck route planning, and noise mitigation across different jurisdictions, such as Riverside County, Moreno Valley, and the City of Riverside. Additionally, this method helps highlight discrepancies and commonalities between local initiatives and broader, statewide legislative efforts like AB 98. Ultimately, content analysis provides valuable insights into how good neighbor guidelines are framed, implemented, and enforced. Based on the coding process, the good neighbor guidelines are each examined across the six localities for their differences and similarities using policy and content analysis.

Policy frame analysis was conducted as part of the coding process to uncover the ideological influences, values, and assumptions embedded in public policy by examining policy texts, legal code, planning documents, and other relevant materials (Doherty, 2007). Frames emphasize specific dimensions of policy issues, and “highlight connections between issues and particular considerations, increasing the likelihood that these considerations will be retrieved when thinking about an issue’’ (Mintz et al., 2003). Framing, whether intentional or unintentional, is a powerful tool in policymaking, and involves the selection of salient policy components to promote a particular problem definition. Analyzing policy text reveals unconscious meanings and ideological underpinnings while providing a clearer understanding of what the policy actually does, beyond its stated intentions.

The changing debate around climate change is an apt example of the importance of policy framing for the understanding and regulation of issues. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the discourse around weather and climate were nearly identical with the words ‘climate’ and ‘weather’ used relatively interchangeably (Hambridge, 1941). This discourse helped to frame climate and weather as local issues, far from the larger considerations of Earth’s global eco and weather systems. However, by the 1970s, new research from MIT and the National Academy of Sciences demonstrated that climate was not merely a local manifestation, but rather a large set of natural processes that occur at the global scale ultimately influenced by the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (SMIC, 1970). Since this frame, where climate and climate change are viewed as global phenomena, came to dominate the discursive field in the 1980s, scientists, policymakers, and the public have “settled on the ‘global pollution’ framing of climate change”, and accepted that inadvertent climate change can occur (Miller, 2000). The use of changing frames over time to organize information and offer an interpretive scheme are commonalities that link both climate change and good neighbor guidelines in general.

II. Local GNGs: Rationales, Frames and Presentation

The stated purposes of policies are important because how a societal problem is defined largely determines what resources are needed for the solution, and can even influence what legislative body will regulate that issue. Therefore, the framing of a policy can be viewed as adding some interpretive flexibility into public policy and the policymaking process, and can additionally change over time as new frames enter into the discursive framework of policy (Ma et al., 2016).

Four (Riverside County, City of Riverside, WRCOG, and City of Lake Elsinore) of the six good neighbor guidelines include a dedicated purpose section. These sections provide background information, relevant rationales, and evidence or research to support the requirements and significance. While there is some variation in the stated purposes, the most common objective is to increase the quality of the environment for communities. More specifically, these guidelines frequently aim to reduce diesel emissions, improve air quality, mitigate impacts on sensitive receptors, and limit noise pollution. Additional purposes include educating the public about the negative effects of industrial facilities, advancing city planning objectives, and preserving neighborhood character. Among the various frames found in current California’s good neighbor guidelines, the most salient and popular are the local environmental frame and the neighborhood character frame.

1. The Local Environmental Frame

The local environmental frame within California’s good neighbor guidelines places emphasis on local environmental integrity and correcting the resultant externalities from increased industrial activity (E.g., increased truck trips, noise pollution, decreased air quality). Every good neighbor policy examined as part of this case study is partially framed as a local environmental measure. For example, Moreno Valley’s guidelines state directly that their policy’s purpose is to “help minimize the impacts of diesel particulate matter (PM) from on-road trucks associated with warehouses and distribution centers on sensitive receptors located within the City of Moreno Valley” (Moreno Valley, 2012?). Yet, there is some variance within the specific environmental factors prioritized in each good neighbor policy, especially over time. This variance in the factors emphasized in the guidelines over time is in part due to evolving standards at different regulatory levels. Between 2005, when WRCOG adopted its policy, and 2016, when Moreno Valley established its own, both the California Air Resources Board and the South Coast Air Quality Management District released standards similar to those found in WRCOG's guidelines. These statewide and/or regional standards reduced the necessity for localities to independently incorporate similar measures into their own good neighbor guidelines. Although the local environment is the most ubiquitous frame in good neighbor guidelines, the neighborhood character frame, while less popular, remains significant.

2. The Maintenance of Community Character Frame

Two policies, the City of Riverside and the City of Lake Elsinore, are framed as measures to maintain, protect and/or preserve community character. Both Riverside and Lake Elsinore present their policies to “protect the residential uses and neighborhood character of the City” and “preserve and advance the City Council’s vision as set forth in the City’s General Plan”, respectively. By framing good neighbor guidelines as mechanisms to maintain community character, the identity of places becomes increasingly important. According to the American Planning Association, community character is defined as, “the distinct identity of a place…the collective impression a neighborhood or town makes on residents and visitors” (Morley, 2018). Using the community character frame, good neighbor guidelines are more than a series of rote land use restrictions, but rather a method to maintain the status quo, or protect the identity of a community, city, or county.

The preservation of community character frame is not exclusively used within the context of good neighbor guidelines, but rather is a common frame used within housing and land use policy more generally. The use of similar frames within land use policy to achieve very different goals seems notable inherently. Both recently and historically, the preservation of community character frame is utilized alongside efforts to maintain the status quo in land use policy; from rote policy delineating methods for preservation of historical properties/land in Colton, California (C. M. C. § 15.40.020), to land use policy to limit the density of housing in St. Paul, Minnesota (to oftentimes low, very low, or estate density) (Brown, 2023). However, within good neighbor guidelines, the maintenance of community character frame is used in conjunction with policy almost solely restricting industrial land uses.

These short examples bring out the interpretive flexibility that can be found in land use policy. Colton’s methods of historical preservation, California’s good neighbor guidelines, and St. Paul's land use policy demonstrate how the framing of a policy can be utilized extremely similarly, if not in an identical manner, yet aim to achieve a diverse set of land use goals. This diversity in policies used in conjunction with the maintenance of community character frame additionally points to the more normative aspects of land use policy. Land use guidelines with extremely similar standards can be normatively viewed very differently within different contexts.

III. Good Neighbor Guidelines in Practice

It should be noted that every local good neighbor guideline in California (known to researchers at the time of this study) has been adopted in the Inland Southern California region, perhaps a result of the increased concentration of warehouses and industrial facilities throughout the region. Additionally, of important note is the influence of the WRCOG’s inaugural good neighbor guideline; many of the requirements, purposes, and the goals of WRCOG’s policy can be found in most subsequent guidelines. Although some guidelines are more similar to WRCOG’s policy than others, the City of Riverside and the City of Moreno Valley’s policies clearly and directly state that their guidelines are a modified version of the original WRCOG good neighbor policy. Although each policy has distinct rationales, goals, and codes, the similarities are germane and salient. The above map provides an overall picture of the implementation of GNG in Southern Inland California.

1. Target Audience of GNG

Several good neighbor policies identified the target audience along with the purpose of the guidelines. Good neighbor policies from WRCOG, City of Riverside, and City of Moreno Valley listed that the guidelines were intended for local government agencies responsible for land use planning and quality, planning departments, property owners, elected officials, community advisory councils or community organizations, and the general public. The remaining good neighbor policies discussed a larger target audience, including community members largely, and residents near warehouses.

2. Sensitive Receptors

Across all good neighbor policies, “sensitive receptors” were identified as the locations affected by the consequences of warehousing and logistics development in the community. Sensitive receptors are primarily defined as spaces where community residents congregate, including residential neighborhoods, schools, parks, playgrounds, day care centers, nursing homes, places of worship, and health facilities such as hospitals. The City of Fontana’s good neighbor policy includes additional spaces such as community centers and prisons. Furthermore, WRCOG, Riverside County, and the City of Fontana specify provisions of additional buffers between newly-built facilities and sensitive receptors. These policies aim to mitigate the detrimental consequences, such as diesel emission exposures, for the identified sensitive receptors within the good neighbor policies. By targeting sensitive receptors, good neighbor policies aim to implement measures that intend to safeguard the health and well-being of community members who frequent these locations.

3. Specific Requirements

The good neighbor policies delineated industrial and warehouse projects that differ in size thresholds by square feet. The City of Fontana has the lowest square feet requirement that requires warehouses greater than 100,000 square feet in size to meet the good neighbor policy requirements. Riverside County’s and the City of Lake Elsinore’s good neighbor policies applied to logistics and warehouse projects that included buildings larger than 250,000 square feet in size. The City of Moreno Valley permitted the largest size applicability by specifying warehouses larger than 650,000 square feet in size under their good neighbor policy. In contrast, WRCOG’s good neighbor policy guidance noted “three or more loading bays, or more than 150 diesel trips per day” in lieu of specifying a size threshold by square feet.

4. Miscellaneous

A direct comparison of the subcomponents and attributes of each good neighbor guideline is included as Figure 3. The categories for noise exposure, construction guidance and signage guidance, refer to specific emphases found within the guidelines. The specific attention to the noise that may be created by industrial facilities is included in each good neighbor guideline - highlighting the different types of pollution that can be created from warehouses, distribution centers, and industrial facilities more broadly. The construction guidance included in the policies varies, with the City of Fontana’s guidelines, for example, requiring parking areas with solar-reflexive pavement and the use of electric-powered hand tools during construction. The signage guidance, the only element of interest that was found in every good neighbor guideline, includes general requirements like anti-idling reminder signs and clearly marked entrance and exit points for truck traffic.

5. Method of Adoption

In a traditional setting, the process to enact a good neighbor guideline is similar, if not a facsimile, to any piece of local policy. Local policies are born out of a confluence of interests, political processes and local circumstances. California cities typically adopt policies, including land use regulations, through a structured process led by the city council. This process for local land use can involve several key steps to ensure transparency, public participation, and compliance with broader legal frameworks, like the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). However, one good neighbor guideline stands out due to the policy’s distinctive enactment process.

The adoption of the City of Fontana’s good neighbor guideline is demonstrative of the recent and larger fight in California for environmental justice through land use. In 2021, Fontana adopted their guidelines in part to settle a CEQA lawsuit filed by the California Attorney General, Rob Bonta. This lawsuit followed the City’s approval of the Slover and Oleander warehouse project, which was criticized for inadequate environmental reviews under CEQA. In addition to the adoption of the city’s good neighbor guidelines, the settlement included community benefits such as improved landscaping around affected schools and the distribution of air filters to nearby households. Commenting on the increased industrial development in South Fontana, Mr. Bonta stated, “for years, warehouse development in Fontana went unchecked, and it’s our most vulnerable communities that have paid the price” (2022).

6. Enforcement

With the exception of WRCOG, all good neighbor policies are legally binding. Local level good neighbor policies are intended to be enforced along with existing land use ordinances, zoning code requirements, and CEQA. These legal frameworks aim to ensure that the policies are integrated into broader urban planning and environmental management strategies, aiming for comprehensive and sustainable community development.

IV. Conclusion & Next Steps

The analysis of California's good neighbor guidelines reveals the critical role these policies can play to address the environmental and social impacts of logistics and warehousing developments. By focusing on issues such as air quality, noise reduction, and traffic management, local GNGs, including those from WRCOG, Riverside County, and the Cities of Moreno Valley and Riverside, provide tailored solutions that reflect local priorities. These guidelines emphasize community engagement and the protection of sensitive receptors like residential neighborhoods, schools, and healthcare facilities, showcasing a commitment to safeguarding public health. Additionally, the use of policy frames such as the local environmental frame and the community character frame highlights how GNGs serve not only as regulatory tools but also as instruments to preserve neighborhood integrity and promote sustainable urban planning. These documents also represent the value of community engagement, the need for proactive environmental measures, and the benefits of aligning development practices with tailored regional guidelines. For planners and policy makers, producing and implementing these guidelines provides the opportunity to address the environmental and social impacts of industrial growth, ultimately fostering sustainable and community-friendly developments.

As the logistics sectors continue to grow, the flexibility and responsiveness of local policies remain essential in balancing economic development with community well-being. However, questions remain about how these policies are implemented, enforced, and the extent to which they have influenced the growth of the logistics and warehousing industries. Examining these processes is particularly important as they may reflect the reception, implementation, and effects of AB 98 in planning and managing logistics and warehousing developments. The next phase of our research will focus on a detailed examination of AB 98 and its relationship with existing local good neighbor guidelines. This upcoming study aims to assess how the statewide standards introduced by AB 98 align with or diverge from local policies, exploring the potential for harmonizing regulations to enhance community protections while supporting economic growth. Additionally, we plan to collect more data from local and regional stakeholders, as well as community members, to evaluate the impacts of existing GNGs comprehensively.

References

Buldeo Rai, H. (2023). Urban warehouses as good neighbors: Findings from a New York

City case study. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 19, 100823-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100823

Cal. Health & Safety Code § 65302.02

Chapter 15.40 - HISTORIC PRESERVATION. Municode Library. (n.d.). https://library.municode.com/ca/colton/codes/code_of_ordinances?

City of Lake Elsinore Council Policy § 400-16

City of Fontana Council Ordinance No. 1891

City of Moreno Valley Municipal Code § 9.05.050

County of Riverside, California Board of Supervisors Policy No. F-3

City of Riverside Community Development Department Planning Division Resolution No. 23639

deSouza, P. N., Ballare, S., & Niemeier, D. A. (2022). The environmental and traffic impacts of warehouses in southern California. Journal of Transport Geography, 104, 103440-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103440

Doherty, R. (2007). Chapter 13: Critically Framing Education Policy: Foucault, Discourse and Governmentality. Counterpoints, 292, 193–204.

González, T., & Saarman, G. (2014). Regulating Pollutants, Negative Externalities, and Good Neighbor Agreements: Who Bears the Burden of Protecting Communities? Ecology Law Quarterly, 41(1), 37–79.

Hambridge, G. W. (1941). Climate and Man: The 1941 Yearbook of Agriculture. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 37(4), 562–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133313497978

Jaller, M., Qian, X., & Zhang, X. (2020). E-commerce, Warehousing and Distribution

Facilities in California: A Dynamic Landscape and the Impacts on Disadvantaged

Communities.

Ma, K. H., & Lee, J. K. (2016). Work and Family Policy Framing & Gender Equality in South Korea: Focusing on the Roh Moo-huyn & Lee Myung- bak Administrations. Development and Society, 45(3), 619–652.

Matthews, W. H., Kellogg, W. W., & Robinson, G. D. (1974). Man’s Impact on the Climate. MIT Press.

Miller, C. (2000). The Dynamics of Framing Environmental Values & Policy: Four Models of Societal Processes. Environmental Values, 9(2), 211–233. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30301731

Mintz, A., & Redd, S. B. (2003). Framing Effects in International Relations. Synthese, 135(2), 193–213. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227118413_Framing_Effects_in_International_Relations

Morley, D. (2018). (rep.). Measuring Community Character. Retrieved 2024, from https://www.planning.org/publications/document/9142842/.

State of California. (2022, April 18). Attorney General Bonta Announces Innovative Settlement with City of Fontana to Address Environmental Injustices in Warehouse Development. Department of Justice. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-bonta-announces-innovative-settlement-city-fontana-address.

Wang, Q., & Kopko, K. (2024). (rep.). The Development of the Logistics & Warehousing Industries in the Inland Region: Opportunities & Challenges. Retrieved December 4, 2024, from https://communitysolutions.ucr.edu/sites/default/files/2024-10/development_logistics_opportunities_challenges_ccs.pdf.

(2005). (rep.). Good Neighbor Guidelines for Siting New and/or Modified Warehouse/Distribution Facilities. Riverside, CA.

Figure 1: Adoption Timeline of Local Level Good Neighbor Guidelines

Figure 2: Attributes of Local Level Good Neighbor Guidelines

By: Kristen Kopko, Jordan Quach, Christina Chu, and Valentina Kiu

January 2025